Gorse is widely known in Aotearoa as our most noxious weed. Much of our grassland is covered in the stuff, it only keeps spreading, and it just looks mean.

It’s literally all thorns.

Neither us nor our farm animals are particularly good at getting rid of it either. Our only way of killing it for good is cutting it down at the root and painting the stump with herbicide – no mean feat considering the nest of thorns that the stem lives in. It's a notably hardy species too, which means it can spread across cliffs and degenerated land, or sprout up from one of its many long-lived seeds the moment we turn our back.

But there's the other side of this story that's often unsaid and unseen.

Gorse is tenacious, able to grow in impoverished soil and lock erosion in place with a dense mat of roots. While it’s there, it fixes nitrogen into the soil and resurrects the microbiome of the soil.

In its shadow, undisturbed by clumsy feet and browsing teeth, native saplings can establish in the newly rich soil. Once these saplings grow into trees, the sun-hungry gorse retreats from their base, making way for shade-tollerant underbrush. It is not identical to its native counterparts – Kānuka and Mānuka – but it is ever more effective at carving land away from us.

We have a nasty habit of only seeing gorse from how we interact with it; a spiny nuisance labelled as ‘invasive’ and free to decimate, but from the perspective of regenerating land it resists our incursion and heals the damage that we have caused. In 30 years, gorse can turn field into forest. It’s an imperfect process, but it works.

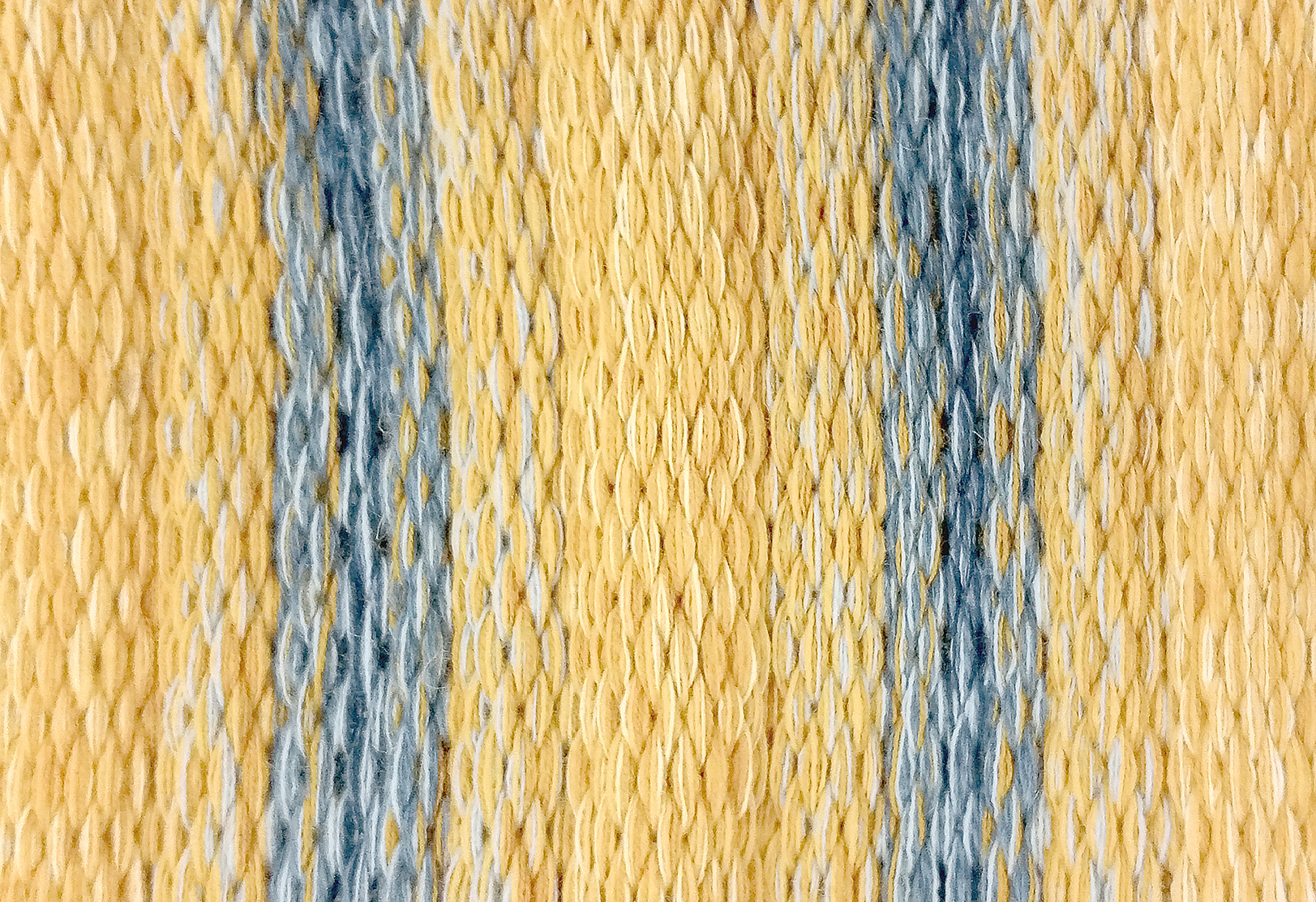

Through natural dye, I created something of a love letter to gorse.

I conducted a series tests – varying concentration, temperature, vat duration, Ph and mordant – to explore something close to the full range of colours that gorse flowers can produce. I then used this guide to dye a wool cloak, representing different aspects of the relationship between the whenua, native species, and gorse. The result is a visualization of gorse on its own terms, so that we may better understand our own complicated relationship to it.

Through this, I explored my own complicated relationship to the land, as a New Zealander, as an Australian, as a migrant, as the ancestor of prisoners and missionaries, and as a queer woman.

My online workbook has all sorts of details on the process and theory if you're interested.

26th of Janurary 2024

Other Projects

2024

2023

2022

-

Through Their Eyes

-

How to Mend with Stabbing

-

Queer Aesthetics

-

Joy in Weave

-

Living Buildings

Then and Now

-

Artefacts

-

Willow the Wisp

A Love-Letter to Gorse